Tuff Stuff's Gamer Winter 1997 - 14 - X-Files CCG, NXT Games & Donruss: Mention - Top of the Order, Red Zone

...NOW PLAY THE CCG!

A representative of the licensor must

approve the game at various stages; large

companies devote whole departments

just to approvals. Sometimes approval is

only a formality, but licensors often exert

their power to protect the property's

integrity. "What you want to do may not

be what they want," Domzalski says.

After seeing the original version of "Star

Trek: The Card Game," for example,

Paramount's licensing official objected

that Kirk, Spock, and McCoy were dying

too easily. So Fleer/SkyBox's designers

"built Band-Aids into the game," Dom-

zalski says, to keep these core crew mem-

bers alive.

Designers must also balance game

play against fidelity to the source. With

the "X-Files" CCG, co-designer Macdonell

says, "Everyone has a very clear expec-

tation of what should occur. Something

weird should happen in the beginning;

FBI agents should be sent to an out-of-

the-way location; they should encounter

mysterious events, unusual witnesses,

and powerful adversaries. Our game had

to play just like that.

A representative of the licensor must

approve the game at various stages; large

companies devote whole departments

just to approvals. Sometimes approval is

only a formality, but licensors often exert

their power to protect the property's

integrity. "What you want to do may not

be what they want," Domzalski says.

After seeing the original version of "Star

Trek: The Card Game," for example,

Paramount's licensing official objected

that Kirk, Spock, and McCoy were dying

too easily. So Fleer/SkyBox's designers

"built Band-Aids into the game," Dom-

zalski says, to keep these core crew mem-

bers alive.

Designers must also balance game

play against fidelity to the source. With

the "X-Files" CCG, co-designer Macdonell

says, "Everyone has a very clear expec-

tation of what should occur. Something

weird should happen in the beginning;

FBI agents should be sent to an out-of-

the-way location; they should encounter

mysterious events, unusual witnesses,

and powerful adversaries. Our game had

to play just like that.

"The major disadvantage of a license is

that you lose some of your creative abili-

ties," Macdonell continues. "Our game is

designed so that mathematically we can

create thousands of unique cards. How-

ever, we can only introduce a new X-File

and/or Agent card if he/she/it makes an

appearance on the show."

The designers of the "Middle-earth:

The Wizards" CCG faced a similar prob-

lem. "We're careful to remain true to the

license," says Fenlon, especially in deal-

ing with Tolkien's fundamental themes.

Nonetheless, "Middle-earth" co-designer

Mike Reynolds says, "We had to create

characters and items to fill out the

playability spectrum. A lot of our fans

find this distasteful." For instance, Mid-

dle-earth has dragons, but Tolkien men-

tioned only two; the "Dragons" expan-

sion invented seven more. According to

Reynolds, some players liked this, but

others said, "If it's not in Tolkien, I don't

want to see it."

that you lose some of your creative abili-

ties," Macdonell continues. "Our game is

designed so that mathematically we can

create thousands of unique cards. How-

ever, we can only introduce a new X-File

and/or Agent card if he/she/it makes an

appearance on the show."

The designers of the "Middle-earth:

The Wizards" CCG faced a similar prob-

lem. "We're careful to remain true to the

license," says Fenlon, especially in deal-

ing with Tolkien's fundamental themes.

Nonetheless, "Middle-earth" co-designer

Mike Reynolds says, "We had to create

characters and items to fill out the

playability spectrum. A lot of our fans

find this distasteful." For instance, Mid-

dle-earth has dragons, but Tolkien men-

tioned only two; the "Dragons" expan-

sion invented seven more. According to

Reynolds, some players liked this, but

others said, "If it's not in Tolkien, I don't

want to see it."

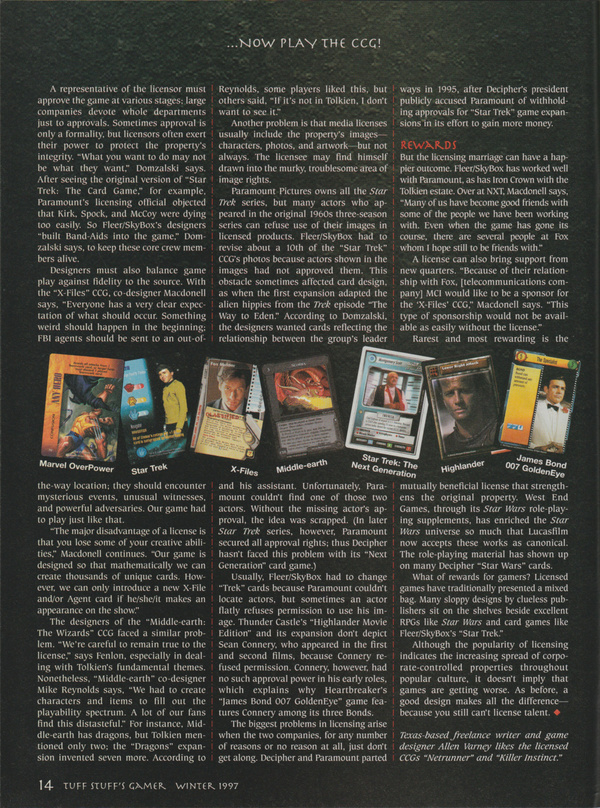

Another problem is that media licenses

usually include the property's images-

characters, photos, and artwork - but not

always. The licensee may find himself

drawn into the murky, troublesome area of

image rights.

Paramount Pictures owns all the Star

Trek series, but many actors who ap-

peared in the original 1960s three-season

series can refuse use of their images in

licensed products. Fleer/SkyBox had to

revise about a 10th of the "Star Trek"

CCG's photos because actors shown in the

images had not approved them. This

obstacle sometimes affected card design,

as when the first expansion adapted the

alien hippies from the Trek episode "The

Way to Eden." According to Domzalski,

the designers wanted cards reflecting the

relationship between the group's leader

and his assistant. Unfortunately, Para-

mount couldn't find one of those two

actors. Without the missing actor's ap-

proval, the idea was scrapped. (In later

Star Trek series, however, Paramount

secured all approval rights; thus Decipher

hasn't faced this problem with its "Next

Gencration" card game.)

usually include the property's images-

characters, photos, and artwork - but not

always. The licensee may find himself

drawn into the murky, troublesome area of

image rights.

Paramount Pictures owns all the Star

Trek series, but many actors who ap-

peared in the original 1960s three-season

series can refuse use of their images in

licensed products. Fleer/SkyBox had to

revise about a 10th of the "Star Trek"

CCG's photos because actors shown in the

images had not approved them. This

obstacle sometimes affected card design,

as when the first expansion adapted the

alien hippies from the Trek episode "The

Way to Eden." According to Domzalski,

the designers wanted cards reflecting the

relationship between the group's leader

and his assistant. Unfortunately, Para-

mount couldn't find one of those two

actors. Without the missing actor's ap-

proval, the idea was scrapped. (In later

Star Trek series, however, Paramount

secured all approval rights; thus Decipher

hasn't faced this problem with its "Next

Gencration" card game.)

Usually, Fleer/SkyBox had to change

"Trek" cards because Paramount couldn't

locate actors, but sometimes an actor

flatly refuses permission to use his im-

age. Thunder Castle's "Highlander Movie

Edition" and its expansion don't depict

Sean Connery, who appeared in the first

and second films, because Connery re-

fused permission. Connery, however, had

no such approval power in his early roles,

which explains why Heartbreaker's

"James Bond 007 GoldenEye" game fea-

tures Connery among its three Bonds.

The biggest problems in licensing arise

when the two companies, for any number

of reasons or no reason at all, just don't

get along. Decipher and Paramount parted

ways in 1995, after Decipher's president

publicly accused Paramount of withhold-

ing approvals for "Star Trek" game expan-

sions in its effort to gain more money.

REWARDS

"Trek" cards because Paramount couldn't

locate actors, but sometimes an actor

flatly refuses permission to use his im-

age. Thunder Castle's "Highlander Movie

Edition" and its expansion don't depict

Sean Connery, who appeared in the first

and second films, because Connery re-

fused permission. Connery, however, had

no such approval power in his early roles,

which explains why Heartbreaker's

"James Bond 007 GoldenEye" game fea-

tures Connery among its three Bonds.

The biggest problems in licensing arise

when the two companies, for any number

of reasons or no reason at all, just don't

get along. Decipher and Paramount parted

ways in 1995, after Decipher's president

publicly accused Paramount of withhold-

ing approvals for "Star Trek" game expan-

sions in its effort to gain more money.

REWARDS

But the licensing marriage can have a hap-

pier outcome. Fleer/SkyBox has worked well

with Paramount, as has Iron Crown with the

Tolkien estate. Over at NXT, Macdonell says,

"Many of us have become good friends with

some of the people we have been working

with. Even when the game has gone its

course, there are several people at Fox

whom I hope still to be friends with."

A license can also bring support from

new quarters. "Because of their relation-

ship with Fox, [telecommunications com-

pany] MCI would like to be a sponsor for

the 'X-Files' CCG," Macdonell says. "This

type of sponsorship would not be avail-

able as easily without the license."

Rarest and most rewarding is the

mutually beneficial license that strength-

ens the original property. West End

Games, through its Star Wars role-play-

ing supplements, has enriched the Star

Wars universe so much that Lucasfilm

now accepts these works as canonical.

The role-playing material has shown up

on many Decipher "Star Wars" cards.

What of rewards for gamers? Licensed

games have traditionally presented a mixed

bag. Many sloppy designs by clueless pub-

lishers sit on the shelves beside excellent

RPGs like Star Wars and card games like

Fleer/SkyBox's "Star Trek."

pier outcome. Fleer/SkyBox has worked well

with Paramount, as has Iron Crown with the

Tolkien estate. Over at NXT, Macdonell says,

"Many of us have become good friends with

some of the people we have been working

with. Even when the game has gone its

course, there are several people at Fox

whom I hope still to be friends with."

A license can also bring support from

new quarters. "Because of their relation-

ship with Fox, [telecommunications com-

pany] MCI would like to be a sponsor for

the 'X-Files' CCG," Macdonell says. "This

type of sponsorship would not be avail-

able as easily without the license."

Rarest and most rewarding is the

mutually beneficial license that strength-

ens the original property. West End

Games, through its Star Wars role-play-

ing supplements, has enriched the Star

Wars universe so much that Lucasfilm

now accepts these works as canonical.

The role-playing material has shown up

on many Decipher "Star Wars" cards.

What of rewards for gamers? Licensed

games have traditionally presented a mixed

bag. Many sloppy designs by clueless pub-

lishers sit on the shelves beside excellent

RPGs like Star Wars and card games like

Fleer/SkyBox's "Star Trek."

Although the popularity of licensing

indicates the increasing spread of corpo-

rate-controlled properties throughout

popular culture, it doesn't imply that

games are getting worse. As before, a

good design makes all the difference -

because you still can't license talent.

Texas-based freelance writer and game

designer Allen Varney likes the licensed

CCGs "Netrunner" and "Killer Instinct."